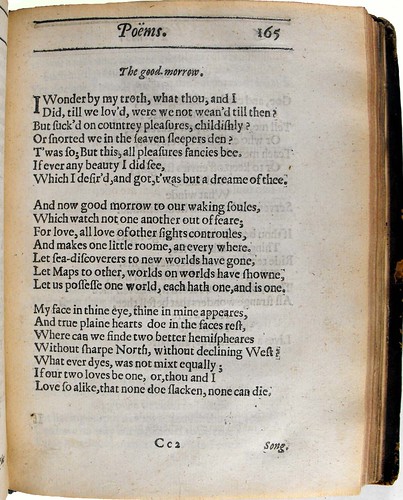

"The

Good-Morrow"

Did, till we lov'd? Were we not

wean'd till then?

But suck'd on countrey pleasures,

childishly?

Or snorted we in the seaven sleepers

den?

T'was so; But this, all pleasures

fancies bee.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desir'd, and got, 'twas but

a dreame of thee.

And now good morrow to our waking

soules,

Which watch not one another out of

feare;

For love, all love of other sights

controules,

And makes one little roome, an every

where.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds

have gone,

Let Maps to other, worlds on worlds

have showne,

Let us possesse one world; each hath

one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine

appeares,

And true plaine hearts doe in the

faces rest,

Where can we finde two better

hemispheares

Without sharpe North, without

declining West?

What ever dyes, was not mixed

equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou

and I

Love so alike, that none doe

slacken, none can die.

The subject.

This is one of Donne's best known

poems, and a perfect sample of his way. The subject is love, love seen as an

intense, absolute experience, which isolates the lovers from reality but gives

them a different kind of awareness; a simultaneous narrowing and widening of reality.

The contents:

The poem is divided in three

stanzas:

- In

the first one the lover rejects the life he led until he met his present love.

He describes it as childish ("were we not weaned,"

"childishly") and unconscious, a kind of sleep ("Or snorted we

in the Seven Sleepers' den"?). His past loves must not be considered as

serious, since he was not completely aware of himself at the time. So, they are

rejected:

. . . But this, all pleasures

fancies be;

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, 'twas but

a dream of thee.

- The

second stanza is, in contrast, a celebration of the present. Each soul has

"awakened" to the other, and has discovered a whole world in it. The

union is self-sufficient; the "little room" where they are is all the

world, "an everywhere." Consequently, the outer world is rejected,

under the symbols of maps and discoverers. Up to now, the poet has cut off his

superfluous experience; past time (the first stanza), external space (2nd

stanza). He seems to be saying "Here and now."

- The

third stanza shows the perfect sincerity and adequation of both lovers, and it

adds a hope for the future to that assertion of the present we have met in the

first stanza. This perfect love is not only immortal: it makes the lovers

immortal, too:

If

our two love be one, or thou and I

Love so alike that none do slacken,

none can die.

3.

Metrical scheme

1 U _ U / U

U _ /_ _

U _ 10 A

_/

U U _/ = U

U _ U _ / 10 B

U

_ U

_ U _ U /

_ U U / 10

A

U

_ U

_ UU_ U _ U _

/ 11 B

5 _

_/ U _ / = _ U

_ U _ / 10 C

U _ U

_ U _ U _

U _ / 10 C

U

_ U _ /

U _ //_ U U _ U _ // 12

C

U

_ _ _

U U UU _ U _ / 11

D

U _

U _ U _ U _ U _ / 10 E

10 U

_ _ _ U _ U _ U _ / 10 D

U

_ U _

U _ U _ U _ / 10

E

__ U _ U

U =_ U _ / 11 F

__ U _

U/_ U _ U _/ 10 F

_

U U _ _ _//_ U _ U_ _// 12 F

15 U

_ U U

= /_ U _ U _/ 11

G

U

_ _ _ U U U _ U _/ 10 H

_

U U _ _ _ U _ U _/ 10 G

U U _ _/ U

U U _ U _/ 10 H

U

_ U _/ _ U UU_ U U/ 10 A

20 U U _ U

U _ / U _ U _ 10

A

_

U U _ U _ U _ U // _ _ _// 12 A

I use (/) to mark internal pauses

and verse pauses; (//) to mark caesura and strophic pause.

This stanza form is not traditional:

it may have been invented by Donne. The decasyllables are used in the sonnet,

but Donne adds a 12-syllable line at the end which gives a nice and nearly

imperceptible variety to the scheme and rounds off the stanza.

It is worth noting that some of the

rhymes have changed sound since the seventeenth century: "one" (line

14) does no longer rhyme with "gone" (line 12) or "shown"

(line 13). The rhymes "childishly"/"I" and

"equally"/"die"/"I" are now imperfect ones.

Although the rhyme in /ai/ resumed at the end of the poem makes Donne repeat

one rhyming word, "I" (1ines 1 and 20), the two instances are far

apart and this is not a major defect in the rhyme-scheme.

Lines 9 and 11 have no real metrical

regularity, unless we pronounce "fear" (line 9) as a monosyllable and

"discoverers" (line 11) in the

relaxed form [dis'k^vr¶z], not suitable to poetic style.

But then syllabic regularity is not essential in English verse, which is mainly

accentual; foreign schemes must adapt themselves to the characteristics of the

English language. Some of the stresses (marked =) would be anomalous in an

Italian or Spanish decasyllable (or rather hendecasyllable), but Donne was

never too careful with this kind of harmony - in Ben Jonson's words, "for

not keeping of accent, he deserved hanging". Donne would not subordinate

the idea to the rhythm. Whether this is a vice or a virtue is a matter of

opinion.

4.

Ornamentation

We are going to examine in the first

place those figures of speech that contribute to enhance musicality, not sense;

those that could be appreciated on hearing the poem even by a person with no

knowledge of English. Of course, the main of these are the metrical scheme and

the rhyme, but these are taken almost for granted in a poem of the seventeenth

century, and deserve a separate section.

- Alliteration is a device

frequently used by Donne. There are several instances in our poem:

Line

2: ". . . Were we not wean'd till then?"

Line

4: "Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den?"

Here

alliteration has an onomatopoeic character; alliteration in - s appears in two words related to sleep,

"snorted" and "sleepers", helping thus to underline the

sense.

- Anaphora in lines 12, 13

and 14; "Let sea-discoverers . . . Let maps . . . let us . . . "

- Epanadiplosis in line 1

(though perhaps a chance one):

"I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I . . . "

- Parallelism of construction

on two occasions:

Line

18: without sharp north, without declining west

PREP ADJ N PREP ADJ N

Line 15: M y face in

thine eye, thine

in mine . . . "

POSS+N PREP POSS+N POSS.Pron. PREP POSS Pron.

Both parallelisms are strongly

emphasized byt the pause in the middle of the line. They appear in association

with other figures, such as

- chiasm: Line 15: My face in thine eye, thine

in mine . . . "

1st p. poss. 2nd. p. poss. 2nd pl. poss. 1st p. poss.

- Reduplication (present too in several other instances):

Line 10: "For love all love

of other sights controls"

Line

13: "Let maps to others, worlds on worlds have shown"

The

word "world" or "worlds" is also present in lines 12 and

14, but the effect is not so conspicuous.

Line

14: "Let us possess one world; each hath one, and is one"

Line

15: "My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears"

(1) (2)

It

is of no consequence that (1) is an adjective while (2) is a pronoun; the

effect is the saqme as far as the ear is concerned.

Line

18: "Without sharp north, without declining west"

Line

21: ". . . love so alike that none do slacken, none can

die"

Now for the figures of speech which

add to the sense: it is in these that Donne's imagination ran more freely:

- Rhetorical interrogative - The

first four lines are a series of these:

-

"I wonder . . .what thou and I / Did, till we lov'd?"

Were we not wean'd till then?

But

sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or

snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den?"

- Exclamation: Line 1:

"by my troth"

- Invocation: In line 8, the

poet addresses himself to his soul and his lover's, and wishes them a

"good-morrow". In fact, the whole of the poem is a sort of

invocation; the poet is speaking to his lady, who doesn't intervene.

- Metonymy: Line 6: "If

ever any beauty I did see"

Beauty = beautiful woman. In fact,

this is everyday speech. The same occurs in lines 8 (souls = minds, people) and

16 (heart=mind, especially if in love). A far more interesing metonymy is

developed in line 14:

"Let us possess one world; each

hath one, and is one".

So, each lover is a world for the

other. If I consider this a metonymy rather than a metaphor, it is because of

Donne's cultural background. At that time it was widely held - it was the

traditional belief - that man was a "microcosm": everything was

ordered in the "macrocosm" or universe just as it was in man; fluids

governed the body just as elements governed the macrocosm; man's destiny was

already fixed in the stars. Knowledge of the world was knowledge of man, and

vice-versa. So it was not difficult for a 17th-century man to think that a

person can assume the proportions of a whole world. Love makes the lover's

attention focus on a part of that great whole. The part is named with the name

of the whole (metonymy).

- Metaphors are fairly

frequent:

Implicit metaphor in lines 2-3

"Were we not wean'd till then? But suck'd on country

pleasures, childishly?" The state of the lovers prior to their falling in

love with each other is identified with childhood. The explicit metaphor would

be "we were babies before we loved".

There is another implicit metaphor

in line 4. It runs much in the same way as the other: "Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den?"

This time, the previous state of

both lovers is identified with sleep. Explicitly: "We were asleep before

we loved".

Line

5: "But this, all pleasures fancies be".

Line 6-7: ". . . any beauty

I did see . . .was but a dream of thee".

This metaphor is the direct

consequence of the one in line 4: if the lover was asleep, it is altogether

fitting that anything he saw should be a dream. It is easy to see how these

metaphors enhance the contents of the poem.

Line 8: "And now good-morrow to

our waking souls".

This is but another extension of the

metaphors in lines 3 and 7. We have already seen that the first stanza deals

with the past, and that the metaphors were those of unconsciousness (childhood

and sleep). The second stanza deals with the present, with the lovers having

discovered one another, and, accordingly, this is dealt with with a metaphor of

waking in the first line of the stanza. "The "good-morrow" with

which Donne addresses the two lovers could be interpreted as a metaphor of the

whole of thie poem, if we suppose the latter to be autobiographical and as

sincere as as it seems to be; the "good-morrow" in the poem is the

lover's rejoicing because of the love he and his lady have found in each other;

"The Good-Morrow" (the poem) amouts to very much the same in real

life. The title would be fully justified.

Line 11: "Love . . . makes one

little room an everywhere".

This is in the same line as the

metonymy "lover = world". The outer world is discarded and the little

room becomes an "everywhere".

Line 16: "And true plain hearts

do in the faces rest".

Sincerity is depicted as a heart

"resting" on a face: no secret intentions for the lovers; their faces

show their hearts. They are externally and internally just as true to one

another.

Lines

17-18: "Where can we find two better hemispheres

Without

sharp north, without declining west?"

The lovers were called

"worlds" in line 14. Now the idea is rounded off; they are not

worlds, they are "hemispheres". This adds three notions to the

previous idea. First, the lovers aren't complete by themselves, they need each

other. A hemisphere is a perfect metaphor for any incomplete thing.

Second, once the lovers are together, they form not only a complete body, but a

whole world (the word "hemisphere" suggests half of the world).

Third, the being they form when they are together is perfect: perfection has

been associated with the spheric shape since Greek times (Democritus,

Parmenides). So the world they form will have no imperfections, no sharp north

or declining west. "Sharp" may stand for quarrels between the lovers,

and "declining" for the gradual decay of love because of time. This

last metaphor opens the way for the final conceit, which states the idea in a

bolder way: immortal love makes the lovers immortal.

This last metaphor is an implicit

one. It is quite complicated, for it takes Donne three lines to develop it:

Whatever

dies, was not mix'd equally;

If

our two loves be one, or thou and I

Love

so alike that none do slacken, none can die.

The first line (19) is, poetically

speaking, rather superfluous, but it is necessary to make the reader understand

the nature of the metaphor that follows. It is an allusion to a scholastic

theory concerning matter, which is based on Aristotle's ideas on heavenly and

sublunary bodies. According to that theory, heavenly bodies are eternal, they

don't change, while sublunary matter is composed of elements in endless

changing combinations and warfare. Sublunary matter cannot reach stability

because it is not "mix'd equally". Donne applies this as a metaphor

of eternal love in lines 20-21. If the total love which is formed with the love

of each of the members of the couple is in perfect poise, that love will be a

perfect body, a heavenly being, and it will never die. If love can never cease,

it means that the couple will go on living and loving each other forever. This

image is very typical of Donne, and a perfect sophism.

So much for the figures of speech.

One more thing to note: the overtly hyperbolic character of the metaphors, in

accordance with the subject of the poem. In line 4, the hyperbole already

present in the metaphor of sleep is rounded out with an allusion to the Seven

Sleepers of Ephesus; these were seven Christian youths who slept for two

hundred years in the cave where they had been immured during Decius'

persecution (AD 251).

5.

Conclusion

The general characteristics we

attributed to Donne's poetry in section 1 are all present in this poem. In

section two, we have seen that it follows one of Donne's two optional views of

love, love as a nearly mystical experience which defies mutability, in contrast

to the cynical attitude of other poems ("The Flea", or "Woman's

Constancy" among the best known). In section 3, the metrical scheme has

proved itself to be original, although slightly imperfect. Donne's poems gain

nevertheless in conversational directness and sincerity what they lack in

rhythm. In section 4 we have observed the imagery to be in perfect tune with

the contents of the poem. Even figures of speech such as parallelism or chiasm

help to underline a sense of reciprocity between the lovers. As for the

metaphors and other figures of thought, they carry Donne's seal. It is

interesting to compare the last and most important metaphor of the poem to

these lines of "A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning":

Dull sublunary lovers love

(Whose soule is sense) cannot admit

Absence, because it doth remove

Those things which elemented it.

The allusion is the same and is used

in much the same way. It is not difficult to understand why Donne was termed a

"metaphysical" poet.

The poem is a moving one: the

emotion it carries can be seen even in the language, which is overtly

emphatical; there are three instances of affirmative clauses with

"do" in only 21 lines (liness 6, 16, 21). Even the adverb

"everywhere" (line 11) is turned into a noun to make the expression

stronger. The impression of totality, of closeness and of rejection of the

outer world that the poem conveys finds here its perfect expression, although

it can be found in other poems by Donne, such as "The Sun Rising",

whose last three lines run thus (the poet is also in a room with his lover,

addressing the sun):

.

. . since thy duties be

To

warm the world, that's done in warming us,

Shine

here to us, and thou art everywhere;

This

bed thy centre is; these walls, thy sphere.

========================================================================

The first stanza

The first stanza of the poem is where the speaker,

who is one of the lovers talking to his partner, looks back to when they were

not in love. That time seems unreal. They were children, naïve, asleep even.

Whatever pleasures they experienced were mere unrealities (‘fancies’) compared

to what they have now. Any beauty (we presume any female beauty) was, again, a

mere dream to be set against the present intense and concrete reality.

The second stanza

The second stanza of the poem suggests that the lovers have woken now into

true reality, out of the shadows of night. In fact, they make their own

reality. The room where they are in bed is their world, and nothing exists

outside its walls. Yes, the poet says, there may be worlds out there: let

discoverers go and find them or map-makers draw them, but let us use our time

possessing our own private world.

The third stanza

One complete world suggests that each is a hemisphere perfectly

complementing the other. The poet concludes by

suggesting that if they can stay totally constant as lovers, then they cannot

die, since, according to current thinking, only what is contrary or of

different measure can disintegrate. A perfect harmony or completeness will be

theirs.========================================================================

Metaphysical Poets

- Metaphysical poems and metaphysical poetry has really

become an epitome of english poetry.

- With poets like John Donne, the tentacles of metaphysical

poetry has really spread far and wide.

- Some popular metaphysical poets of seventeenth century

are DONNE,VAUGHAN, MARVELL and

TRAHERNE, and popular figures like ABRAHAM COWLEY are

sometimes included in the list.

I WONDER by my troth, what thou and

I

Did, till we loved ? were we not wean'd till then ?

But suck'd on country pleasures, childishly ?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den ?

'Twas so ; but this, all pleasures fancies be ;

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, 'twas but a dream of thee.

Did, till we loved ? were we not wean'd till then ?

But suck'd on country pleasures, childishly ?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den ?

'Twas so ; but this, all pleasures fancies be ;

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, 'twas but a dream of thee.

Understanding

the Theme of the poem Good Morrow by John Donne

- This Good Morrow meaning will help the readers in understanding the link

which:-

- Donne draws from medieval alchemy towards the end of

the poem to explain the immortality of the love which he shares with his

beloved.

- The poet says to his loved one that their love is

indestructible since it is pure.

- It is the hardest to relax the bonds of pure

substances.

- The mixing of two things causes impurity which

threatens the longevity of substances.

- The lovers do not feel this threat since their love is

not mixed with any selfish demands or intentions of any kind and is

perfectly pure.

- With such a strong bond of love between them the poet

is convinced that nothing can ever decrease or stop the stream of love

which flows between his beloved and him.

The

Good Morrow Meaning - Stanza One

- In the beginning of the Good morrow

poem, the poet asks his beloved how they used to spend their

lives before they had met each other. With his beloved in arms, the poet

realizes how empty his life was before he had met her. He considers that

phase of their lives to be as meaningless as the ones spent in slumber by

the seven sleepers of Ephesus in the den when they were trying to escape

wrath of the tyrant Emperor Decius. Being without his beloved was as

insignificant as those years which the seven sleepers had spent sleeping.

It means that those years bore no importance in his life anymore. During

those days when he was yet to discover true love, he would make up for

that emptiness by indulging in other pleasures of life but now after

understanding the meaning of love he realizes that those pleasures were

very artificial. Now it seems to the poet as if he was a small child

during those days who was being weaned on these materialistic pleasures

of the world in the absence of true love which was like mother’s milk to

that child. During those days all objects of beauty that he came across

were nothing but her beloved’s reflection. To the poet her beloved was

like a beautiful dream which was turned into reality. In this Good

morrow analysisit is worth mentioning that through false pleasures

the poet might be indicating towards his various liaisons with other

women which were just a reflection of the beauty which his true lover filled

him with.

And now good-morrow to our waking

souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear ;

For love all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone ;

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown ;

Let us possess one world ; each hath one, and is one.

Which watch not one another out of fear ;

For love all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone ;

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown ;

Let us possess one world ; each hath one, and is one.

The

Good Morrow Poem Analysis - Stanza Two

- In the second stanza of “The good morrow” the

poet sheds light upon the bliss which envelops the lovers. He says that

their souls rise in the light of the new morning of love in their lives.

Their hearts are devoid of any kind of fear of commitment,

misunderstanding or losing the one they love. Their presence in the each

other’s life means so much to them that nothing catches their attention

anymore. Donne proposes his loved one to turn their tiny room in which

they make love into their only world. He says that he does not care about

how much the sea discoverers expand the boundaries of the world with their

discoveries. During those times when maritime discoveries were given

utmost importance, the new inclusions to the map of the world meant

nothing to the poet since his world only comprised of his beloved and

him.Their respective worlds have now been fused into one. This drawing of

an intellectual parallel from astronomy and geography strengthens the

metaphysics of the poem.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine

appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest ;

Where can we find two better hemispheres

Without sharp north, without declining west ?

Whatever dies, was not mix'd equally ;

If our two loves be one, or thou and I

Love so alike that none can slacken, none can die.

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest ;

Where can we find two better hemispheres

Without sharp north, without declining west ?

Whatever dies, was not mix'd equally ;

If our two loves be one, or thou and I

Love so alike that none can slacken, none can die.

Summary

of Good Morrow - Stanza Three

- Next the poet talks about theunique beauty of the

lovewhich he and his beloved share. Donne says that that sometimes he

and his beloved stare into each other’s eyes so longingly that they can

see their faces in the other’s eyes. This refection of faces in the eyes

reveals the true hearts of the lovers. Their hearts are true and spotless

in love. This means that their love for each other enables the lovers to

get rid of all their bad traits and harsh feelings towards the world which

helps them become better people. The poet further adds that unlike the

world which is divided in hemispheres, their world of love knows no

boundaries. It does not have a sharp cold northern hemisphere. Nor does it

have a western hemisphere which has to bid farewell to the sun. By drawing

this reference to Geography again, the poet tries to give us an insight

into theunparalleled bliss of his world of love where it is

always warm and sunny.

Conclusion

to the poem The Good Morrow

Thus through “The Good

morrow” we see that love is capable of elevating a person to new

heights from where he views his love and the world around him in a different

light.

1 comments:

Only poets in the caliber of Donne can compose such a powerful love lyric. In a sense, the poem transcends the usual pattern of love poetry. There is in fact a deep insight into varied philosophical matters on human life in general. Donne the poet is also a great philosopher of human emotions and conditions.

Best Custom Essay Writing Service

Post a Comment